- Introduction and background

- Part 1: Legal frameworks

- Part 2: Policies and procedures

- Part 3: Comparative indicators

- Summary and recommendations

- References and data sources

Introduction

Reporting period: 2022

Report author(s): Joel F. Ariate Jr., Marion Abilene R. Navarro, Nixcharl C. Noriega

Summary: Despite having legal frameworks that meet international standards, the data for the 2022 monitor shows that the Philippines had excessive use of lethal force, with much room for improvement in data collection and transparency by official agencies.

Abstract

Comparative indicators on the use and abuse of lethal force in the Philippines for 2022 indicate that law enforcement agents in the country use disproportionate and excessive force. This finding is drawn from a database that gathered online news accounts of deaths and injuries involving law enforcement agents. Of the 876 individual cases examined, 389 were killed by gunshot by on-duty law enforcement agents, that is 0.34 per 100,000 civilian inhabitants and the ratio of civilians killed by gunshot by on-duty law enforcement agents to the total number of homicides in the country is 389:1,015 or 0.38, which are both higher compared to other countries.

There is also a lack of publicly accessible official, governmental data on the use of force. Data collection is highly reliant on media reports and on posts on official social media pages of law enforcement agencies or government-controlled newswires. Independent monitoring by civil society organizations or academic institutions, unaffiliated with the agencies, have also dwindled in the past years. As a consequence, some indicators cannot be computed due to the lack of data, such as the total number of armed uniformed personnel employed by the government, or the rates of lethal force separated by gender and ethnicity. Philippine laws provide for oversight and investigative bodies on the use of lethal force by law enforcement agencies, but a culture of impunity and violence trumps the letter of the law. Investigations on deaths involving law enforcement agents are limited, and implementation of recommendations based on completed independent investigations is not well supported. The country has also revoked its membership of the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Background

As provided for in Republic Act (RA) 6975, enacted on 13 December 1990, the Philippine National Police (PNP) “that is national in scope and civilian in character” and falls under the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), has as one of its primary powers and functions the enforcement of “all laws and ordinances relative to the protection of lives and property”. The PNP is also mandated to “maintain peace and order and take all necessary steps to ensure public safety; investigate and prevent crimes, effect the arrest of criminal offenders, bring offenders to justice and assist in their prosecution” as well as “exercise the general powers to make arrest, search and seizure in accordance with the Constitution and pertinent laws”. The law implies that in discharging these duties, the police may resort to lethal force.

Over the years, the authority to bear firearms and to use lethal force while enforcing the law has been extended to various other units, some falling under the DILG, while others draw their authority from other executive offices (that is, offices which are under presidential command and control). A few, like the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) and the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA), are directly under the Office of the President.

Besides the PNP, other personnel under the DILG provided with service firearms are select members of the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP) and the Bureau of Fire Protection (BFP) who have law enforcement functions. The same is true for those under the Department of Justice (DOJ), in particular members of the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI), the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor), and the Bureau of Immigration (BI). The PNP, the BJMP, the NBI, the BuCor, and the BI all have detention facilities. For the period covered in this report, cases of suspicious deaths or those reported as homicide, were recorded only for those under the custody of the PNP. There were also cases of police officers getting assaulted and even killed, by persons they have imprisoned. Of the 389 civilians killed by gunshot by on-duty law enforcement agents, three were in police custody1: They attempted to escape; two were immediately killed after stabbing a police officer, the third was killed after taking another prisoner hostage.

Some members of the Bureau of Customs, which is under the Department of Finance, are also allowed to carry firearms. In the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, a select few from the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority have service firearms. Members of the Philippine Coast Guard, which is under the Department of Transportation, are also armed.

Besides the PNP, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) is the other significant agency whose members are authorized to carry firearms in the conduct of their duty. Falling under the Department of National Defence, the AFP is supposed to focus on external threats, where the PNP deals with internal ones. But given half a century of rebellion and insurgency in the Philippines, this line has been blurred. Hence RA 8551, enacted on February 25, 1998, states that “the Department of the Interior and Local Government shall be relieved of the primary responsibility on matters involving the suppression of insurgency and other serious threats to national security. The Philippine National Police shall, through information gathering and performance of its ordinary police functions, support the Armed Forces of the Philippines on matters involving suppression of insurgency, except in cases where the President shall call on the PNP to support the AFP in combat operations”.

As is apparent, the inclusion of other LEAs apart from the PNP is necessary because implementation of different police intervention campaigns is executed through interagency efforts.

Due to the intense and widespread use of lethal force in the Philippines, this report will only focus on incidents occurring in the country in the year 2022. To address the lack of official sources of data, a database was devised through independent media reports and postings from local units of LEAs matching a set collection of inclusion and exclusion criteria: Foremost, that each death or injury recorded in the Monitor involved a law enforcement agent (whether as victim or perpetrator), and that it was inflicted using a gun. Other data used to compute indicators of lethal force use were obtained through official reports for 2022, such as World Bank Data and the PNP 2022 Annual Accomplishment Report.

Part 1: Legal Frameworks

Global treaties

| 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) | State party | |

| ICCPR Optional Protocol 1 | State party | |

| 1984 Convention Against Torture (CAT) | State party | |

| CAT committee competent to receive individual complaints? | No | |

| CAT Optional Protocol 1 | State party | |

Regional treaties

| 2013 ASEAN Human Rights Declaration | Yes | |

National legal provisions

Relevant constitutional provisions or general laws

Constitutional provisions relevant to the state’s use of force may be found under Article II of the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines containing the state’s guiding principles, such as “[t]he maintenance of peace and order, the protection of life, liberty, and property, and the promotion of the general welfare” (Section 5)2. Relevant provisions may also be found in Article III or the Bill of Rights which includes, among others, Section 1 stating that “[no] person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws”3.

The general penal laws of the Philippines are found in the Revised Penal Code4. Relevant provisions with regard to the use of force may be found in Title Eight: Crimes Against Persons. More specifically, chapter one enumerates the corresponding penalties for crimes that constitute the destruction of life such as murder and homicide, while chapter two contains the provisions penalizing crimes related to inflicting physical injuries.

Relevant specific national legislation

As of date, there is no specific national legislation regulating the use of force particularly in the context of a law enforcement operation. For instance, provisions in Republic Act 69755 titled the “Department of the Interior and Local Government Act of 1990” that established the Philippine National Police under a re-organized department only outlines in general the functions of the police force. Before RA 6975 took effect in 1991, the police force called the Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police, was part of the Armed Force of the Philippines under the Department of National Defense. From 1991 until today, the PNP has been under the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), to emphasize its civilian nature and the fact that it is under civilian control. RA 6975 also created the National Police Commission under the DILG to examine and audit the standards of policing and compile “statistical data for the proper evaluation of the efficiency and effectiveness of all police units in the country”.

In 1998, some parts of RA 6975 were amended by virtue of RA 8551. Of note was the creation of an Internal Affairs Service within the PNP. Its primary tasks: “pro-actively conduct inspections and audits on PNP personnel and units; investigate complaints and gather evidence in support of an open investigation; conduct summary hearings on PNP members facing administrative charges; submit a periodic report on the assessment, analysis, and evaluation of the character and behavior of PNP personnel and units to the Chief PNP and the Commission; file appropriate criminal cases against PNP members before the court as evidence warrants and assist in the prosecution of the case; and provide assistance to the Office of the Ombudsman in cases involving the personnel of the PNP”.

RA 8551 specifically authorizes the IAS to “conduct, motu proprio, automatic investigation of the following cases: incidents where a police personnel discharges a firearm; incidents where death, serious physical injury, or any violation of human rights occurred in the conduct of a police operation; incidents where evidence was compromised, tampered with, obliterated, or lost while in the custody of police personnel; incidents where a suspect in the custody of the police was seriously injured; and incidents where the established rules of engagement have been violated”. Yet its annual report for 2022 offers no details on what it has accomplished on the aforementioned mandates, except to make a claim that it has a “100% case resolution”6.

Relevant national regulations

Extensive guidelines on the use of force by law enforcement officers are found in the Philippine National Police Manual containing the operational procedures the force must abide by. In the most recent version of the manual, dated September 2021, the Revised Philippine National Operational Procedures, Section 2–4 sets out the police policy on the use of force. The manual implements a ‘Use of Force Continuum’, defined as “a linear-progressive decision-making process which displays the array of police reasonable responses commensurate to the level of suspect/law offender’s resistance to effect compliance, arrest and other law enforcement actions”7. Three approaches are enumerated in the continuum corresponding to the perceived level of threat: 1) non-lethal approach; 2) less-lethal approach; and 3) lethal approach. The lethal approach is prescribed as the “last resort”8 that is only employed during life-threatening situations such as instances where the suspect is armed and shows unlawful aggression against police or other individuals. The use of firearms is justified in the lethal approach, but officers are ordered to avoid hitting vital parts of the body and provide immediate medical attention to the suspect. The manual also requires police officers to submit an incident report for every use of service firearm or weapon. The Use of Force Continuum is also written into the PNP Guidebook on Human Rights Based-Policing9.

Legal interpretation and application

UN or other international body decisions or advisory opinions

The Philippines has declared its adherence to key global human rights treaties relevant to the state’s use of force, particularly: the 1966 Covenant on Civil and Political Rights10 (ICCPR, ratified 23 October 1986); the ICCPR Optional Protocol11 (ratified 20 November 2007); the 1984 Convention Against Torture12, 13 (CAT, ratified 18 June 1986) including its Optional Protocol 114 (ratified 17 April 2012). The Philippines was originally a state party to the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, but announced its withdrawal under former President Rodrigo Duterte in March 201815, which formally came into effect a year later. This was in response to the International Criminal Court’s February 2018 announcement that it would launch a preliminary investigation for possible crimes against humanity committed in the country, particularly in the context of its campaign against illegal drugs. On 14 May 2021 its Pre-Trial Chamber authorized the investigation for crimes against humanity in the implementation of the country’s drug war, covering the period 1 November 2011 to 16 March 2019, for which the ICC asserts its jurisdiction given that the alleged crimes happened while the Philippines was a State Party to the Rome Statute. The resumption of the investigation went back and forth due to the Philippine state’s efforts to block it. The Philippine government’s most recent appeal to the ICC, filed in February 2023, to block its investigation of possible crimes against humanity committed in the Philippines was rejected by the ICC in July 2023. The ICC deems the probe as continuing and in effect16.

In 2016, the former president Rodrigo Duterte launched an anti-illegal drug campaign “War on Drugs” or “Oplan Tokhang” as one of his government’s flagship programs, which in effect gives officers a license to kill. The ICC issued a statement of concern17 and has been monitoring human rights violations in relation to the program since 2016, despite threats by the president at that time to withdraw from the ICC. In 2017, a whistleblower of the Davao Death Squad prompted the filing of a petition for preliminary examination by the ICC. In 2018, the ICC initiated preliminary investigations18 on the “War on Drugs” and in the same year, the Philippines submitted a written notice of withdrawal from the Rome Statute19. From 2019 to 2022, the ICC has continued investigations against the Duterte government for Crimes Against Humanity, with limited progress. The investigation was resumed in 2022 at the beginning of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr.’s term. In 2023, the ICC pre-trial chamber re-opened the investigation, and in response the Philippine government filed a motion to block investigations20. In the most recent development in July 2023, the ICC rejected the appeal. However, the current administration refuses to cooperate with the ICC probes21.

Regional court judgments

The Philippines is a member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) which promulgated its own ASEAN Human Rights Declaration in 2013 to affirm the association’s commitment to upholding human rights in the region. The declaration reaffirms adherence to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Declaration of the Advancement of Women in the ASEAN Region, and the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women in the ASEAN Region22.

The Declaration is non-binding, in most part due to the principle of non-interference in each of the member states’ internal affairs. There are therefore no regional human rights court judgements based on it.

Still, the declaration provides a human rights framework for ASEAN member states to follow. The implementation of the declaration is supported by the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights which recently convened in March 2023 to discuss developments in the human rights situation in the ASEAN region23.

National court judgments

In 2023, the Philippine National Police Internal Affairs Service (PNP IAS) ordered the relief of six police officers and that criminal complaints were filed against them for reckless imprudence involving homicide after shooting a minor, Jemboy Baltazar, who was mistaken for another suspect. The officers also failed to comply with regulations on wearing body cameras during operations. There are no publicly available records on the proceedings of the prosecution against the six LEOs. Relief from a post or an office is a temporary disciplinary measure in the police force. As provided for by RA 8551, “a PNP uniformed personnel who has been relieved for just cause and has not been given an assignment within two (2) years after such relief shall be retired or separated”.

In 2021, the Department of Justice dismissed murder complaints against 17 police who were involved in the killing of nine activists in the incident called “Bloody Sunday”, due to “lack of merit”.

In 2018, Caloocan Regional Trial Court Branch 125 held three policemen guilty of homicide against a minor, Kian Delos Santos, who was killed in the “War on Drugs” for allegedly being involved in the drug trade and fighting the police during official operations. Evidence, however, shows that he was killed unarmed and was pleading for his life24.

Oversight bodies

The Republic Act No. 6770, or “The Ombudsman Act of 1989”, gave the Ombudsman and his/her deputies the mandate that they “shall act promptly on complaints filed in any form or manner against officers or employees of the Government, or of any subdivision, agency or instrumentality thereof, including government-owned or controlled corporations, and enforce their administrative, civil and criminal liability in every case where the evidence warrants in order to promote efficient service by the Government to the people”. Republic Act No. 6770 assigns the Office of the Deputy for the Armed Forces, now the Office of the Deputy Ombudsman for the Military and Other Law Enforcement Offices (OMB-MOLEO), to prosecute cases involving law enforcement agents and other uniformed personnel.

When the Department of the Interior and Local Government was established in 1990 by virtue of Republic Act No. 6975, the same law provided that a National Police Commission (NAPOLCOM) shall “exercise administrative control over the Philippine National Police”. It was empowered to “affirm, reverse or modify, through the National Appellate Board, personnel disciplinary actions involving demotion or dismissal from the service imposed upon members of the Philippine National Police by the Chief of the Philippine National Police”.

Republic Act No. 8551 or the “Philippine National Police Reform and Reorganization Act of 1998” created the Internal Affairs Service (IAS) of the PNP. Among its enumerated functions, the IAS, on its own accord, “shall also conduct … automatic investigation of the following cases: a) incidents where a police personnel discharges a firearm; b) incidents where death, serious physical injury, or any violation of human rights occurred in the conduct of a police operation; c) incidents where evidence was compromised, tampered with, obliterated, or lost while in the custody of police personnel; d) incidents where a suspect in the custody of the police was seriously injured; and e) incidents where the established rules of engagement have been violated”.

The IAS may recommend “the imposition of disciplinary measures against an erring PNP personnel”. The IAS’s recommendation “cannot be revised, set-aside, or unduly delayed by any disciplining authority without just cause”. The IAS can file a case against a member of the PNP in the appropriate court and it can “provide assistance to the Office of the Ombudsman in cases involving the personnel of the PNP”. What IAS does not have is the power to prosecute and try cases that it has been tasked to investigate. It is also perceived to be tainted by the corruption that engulfs the PNP25. And in September 2022, a sexual harassment case was filed against the head of the IAS before the Office of the Ombudsman26. The IAS inspector general was convicted of the charge27.

In 2009, NAPOLCOM established the Philippine National Police Human Rights Desk to monitor and consolidate reports on human rights violations allegedly committed by state and non-state actors. Based on the Philippine National Police Human Rights Desk Operations Manual, the PNP HRD is required to submit monthly reports of human rights violations to the PNP Human Rights Affairs Office. The Desk, however, does not have investigative functions28.

Besides NAPOLCOM and the PNP’s IAS, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the Department of Justice are oversight bodies that investigate police misconduct. The CHR was established by the 1987 Philippine Constitution through Executive Order No. 163. The Commission is mandated to ensure the protection and promotion of human rights in the country. To do this, the Commission is mandated to conduct investigations, on its own or in response to complaints, on incidents that involve “all forms of human rights violations involving civil and political rights”. The CHR has the court’s power to cite for contempt those who unduly challenge or defy its investigations and it has “visitorial powers over jails, prisons, or detentions facilities”. Yet, as with the IAS, it can only recommend prosecution to other executive and constitutional offices like the Department of Justice or the Ombudsman.

The Philippines, it seems, has various institutions for redress for victims of violence by law enforcement agents and uniformed personnel. The question is whether they work as intended or whether they were intended not to work at all.

Part 2: Policies and Procedures

Data collection and publication by official agencies

| 1. Are the number of deaths following any police use of force | ||

| Collected? | Unknown | |

| Accessible through existing publicly available information? | Limited, Poor | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | Good, Robust | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | Not applicable | |

| 3. Is it possible to identify specific individuals killed in official records? | Unknown | |

| 4. Is demographic and other information for the deceased | ||

| Collected? | Unknown | |

| Accessible through existing publicly available information? | Limited, Poor | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | Good, Robust | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | Limited, Poor | |

| 5. Is demographic and other information on officers in use of force incidents | ||

| Collected? | Unknown | |

| Accessible through existing publicly available information? | No Provisions | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | Unknown | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | No Provisions | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | No Provisions | |

| 6. Is information on the circumstances | ||

| Collected? | Unknown | |

| Publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | Good, Robust | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | Limited, Poor | |

| 7. Is information about the type(s) of force used | ||

| Collected? | Unknown | |

| Accessible through existing publicly available information? | No Provisions | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | No Provisions | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | No Provisions | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | No Provisions | |

Data quality of official sources

| 8. How reliable are the sources used to produce official statistics about deaths? | No Provisions | |

| 9. Are there mechanisms for internal quality assurance / verification conducted | Unknown | |

| 10. Is the methodology for data collection publicised? | No Provisions | |

| 11. How reliable are the overall figures produced? | No Provisions | |

Data analysis and lessons learnt

| 12. Do state or police agencies analyse data on the use of lethal force, to prevent future deaths? | Unknown | |

| 13. Is there evidence that state/ police agencies act on the results of their analysis, including applying lessons learnt? | Limited, Poor | |

| 14. Are external bodies are able to reuse data for their own analyses? | Limited, Poor | |

| 15. Do external, non-governmental agencies collect and publish their own statistics on deaths following police use of force? | Partial, Medium | |

Investigations by official agencies

| 16. Is there a legal requirement for deaths to be independently investigated? | Partial, Medium | |

| 17. If so, which organisation(s) conduct these investigations? | Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) | |

| 18. In the year in question, how many deaths following police use of force have been investigated by the organisation(s) specified in question 17? | Data unavailable | |

| 19. Are close relatives of the victims involved in the investigations? | Unknown | |

| 20. Investigation reports into deaths | ||

| Are publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| Give reasons for the conclusions they have reached? | Limited, Poor | |

| Is this a legal requirement? | Good, Robust | |

| Can such information be requested from the authorities when not publicly available? | Limited, Poor | |

| If one can request it, what is the likelihood this information would be released? | Limited, Poor | |

| 21. Is there information available on legal proceedings against agents / officials, pursuant to deaths? | Limited, Poor | |

| 22. Is there information available on legal proceedings against state agencies, pursuant to deaths? | Partial, Medium | |

| 23. Is there information available on disciplinary proceedings against agents/ officials, pursuant to deaths? | Unknown | |

| 24. Number of prosecutions against agents / officials involved in the last ten years? | Data unavailable | |

| 25. Number of convictions against agents / officials involved in the last ten years? | Data unavailable | |

| 26. Number of prosecutions against agencies involved in the last ten years? | Data unavailable | |

| 27. Number of convictions against agencies involved in the last ten years? | Data unavailable | |

| 28. Number of cases in which states have been found to have breached human rights law on the use of lethal force? | Data unavailable | |

Detailed elaboration

Data collection and publication by official agencies

Based on the PNP Standard Operating Procedures and the PNP Manual, the PNP is required to maintain a handwritten journal of all operational and administrative activities that includes all crime incident reports and arrests. The report should include the names of those involved in the incident (including victims, suspects, witnesses, and other individuals present in the scene), time and date of incident, location of incident, specific happenings during the incident, alleged motive, incident narrative, and details of the reporting officer. This is submitted together with an incident record form and included in the PNP Incident Recording System29. However, the PNP or other law enforcement agencies in the Philippines do not release aggregate statistics on police use of force for all police interventions. Those that specifically involve the use of force, often lethal, by the police, should have been investigated automatically by the PNP’s Internal Affairs Service. As mentioned above, the IAS did not mention these cases under their investigation nor the ones resolved in their publicly accessible annual report.

Previously, the PNP released statistics specifically for the anti-illegal drug campaign as one of the flagship programs of the previous administration under former president Rodrigo Duterte. This data was posted through the #RealNumbersPH, a government controlled Facebook page that serves as the “government’s unitary report on the campaign towards a drug-free PH”30. The publication of this data however, was discontinued after June 2022 when current president Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr. took office.

Currently, there are no publicly available aggregate statistics or a centralized database on police use of force in the country. Incident reports from PNP and specific details of operations are included in the detailed list of PNP exceptions to the Freedom of Information31.

Though some information on the police’s use of force and its consequences can be gathered from the PNP’s Annual Accomplishment Report, these data may have been stated in a different context. In the PNP’s 2022 report32, one can read in the section on “Morale and Welfare Program”, that “a total of 42 KIPO and 142 WIPO were assisted to expedite the release of claims intended for their beneficiaries”. KIPOs are killed in police operations, WIPOs are wounded in police operations. The 2022 report also has a section on “Improved Crime Solution” where, in one of the bar graphs, one can read that in 2021 there were 4,851 murder in the Philippines, while in 2022, there were 4,272. Homicide in 2021 was at 1,131; in 2022, there were 1,015. These are salient data on the police’s use of force.

Data in the Accomplishment Report are also not segregated by sex or ethnicity. There were previous attempts to request official statistics on deaths during specific police operations — such as in the case of anti-illegal drug campaigns, — through FOI before it was listed as an exception. However, released reports usually include figures that are lower than those reported by academic and human rights organizations which independently monitor drug-related killings33.

While aggregate statistics are unavailable, there are individual incident reports posted via official Facebook pages of the PNP regional or local units or government newswires such as the Philippine News Agency (PNA) and Philippine Information Agency (PIA). These cases are usually reported by local media outlets, which are disseminated through Facebook pages or websites. However, these need to be manually collated and cross-checked, which is an endeavour not mandated to any government institution but that academic or private organizations take on. For law enforcement agencies, academic institutions or NGOs in the Philippines, dissemination of public information is heavily reliant on Facebook, hence its importance as a data source.

Data quality of official sources

There are no publicly available statistics on the use of police force in the Philippines for the year 2022. It is reasonable to assume that the PNP and other law enforcement agencies have their own records of deaths and injuries of public security agents (PSAs) in the conduct of their duties. If they do, there is no public document on how the data is collected and verified. Efforts to access data that pertain to police and military matters through freedom of information requests are generally known to be denied. In the 2021 People’s Freedom of Information (FOI) Manual of the Philippine National Police, for example, there is a lengthy list of matters exempted from right of access to information, in particular information involving investigation and intelligence.

Data analysis and lessons learned

The PNP Human Rights Affairs Office was activated in 2007 through Resolution Number 2007-247 of the National Police Commission. Some of the functions of the PNP HRAO include: “Review, formulate, and recommend human rights policies & programs including administrative & legal measures on human rights” and “Monitor investigations and legal/judicial processes related to human rights violations” 34.

However, the last Accomplishment Report of the office posted on their website was in 202035. In the report it was mentioned that the PNP HRAO conducted a series of forums with civil society organizations, to discuss police use of force and human rights concerns including issues of arrest and ill treatment. Possible administrative approaches to address problems with police use of force were discussed. The PNP HRAO did not name the civil society organizations that participated in these forums, except to say that there were “a total of 756 attendees from the PNP, CSO, and concerned government agencies”. The forums were conducted in partnership with Germany’s Hanns Seidel Foundation.

Investigations by official agencies

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) are agencies mandated by the Philippine Constitution to conduct independent investigations on police misconduct and human rights violations. There are problems, however, in the implementation of the recommendations based on these investigations.

The CHR conducted an independent investigation on the police use of force during the War on Drugs from 2016 to 2021, which was released to the public in April 2022. The report stated the “use of excessive and disproportionate force is also evident in 329 incidents”36. The report included detailed recommendations, including that the “Philippine National Police (PNP), including PNP-IAS, conduct full, immediate, thorough, transparent and impartial investigations on drug-related extrajudicial killings particularly deaths during anti-drug operations, deaths while in custody/detention, and administrative cases pending before them”37. This recommendation is reliant on participation and cooperation from the police. Another recommendation from the report was that the “Department of Justice (DOJ), as the principal law agency and legal counsel of the government, investigate the cases involving drug-related extrajudicial killings through the National Bureau of Investigation and prosecute persons charged with the commission of these extrajudicial killings through the National Prosecution Service”38. The DOJ is conducting investigations on the cases of extrajudicial killings. At the time of writing this report, there was no update available on the investigations. The CHR is also not included in the current review panel of the said investigations, but has stated interest in participating if invited.

The issue of extrajudicial killings in the context of the “War on Drugs” is of international interest and is being investigated by the International Criminal Court. The Philippine government, however, has expressed unwillingness to cooperate with the said investigations. The Marcos government that succeeded the Duterte administration has repeatedly justified its non-cooperation with the ICC on the grounds that it is “an intrusion into our internal matters and a threat to our sovereignty”39.

Legal proceedings, prosecutions and convictions

Apart from the War on Drugs, there are cases of police misconduct that have led to criminal and administrative charges against police (detailed in Part 3). However, public dissemination of the results of the investigations are heavily reliant on media outlets based on public demand on select cases. As is apparent in recent cases, if the killing by the police of an unarmed civilian is caught on camera, whether on a mobile phone or CCTV, and goes viral in the social media, then usually a strong public condemnation follows along with continuing interest as to whether the killer cops will ever be tried and convicted in a court of law. There is also no centralized database or official statistics on the number of prosecutions or convictions against agents or officials, in 2022 or in the last 10 years.

The total number of cases in which the State has been found to have breached human rights law is unknown, but the International Criminal Court (ICC) is currently investigating the “War on Drugs” killings 2016–2019 during the Rodrigo Duterte administration as possible crimes against humanity. Also included in the ICC investigation are the killings in Davao City, 2011–2016 when it was administered by Duterte.

Non-official sources

Due to the lack of aggregate statistics, monitoring of police use of force is heavily reliant on media reports. Cases of deaths and injuries involving law enforcement agents are usually reported through media outlets and posted through their Facebook pages. While some of these reports reach national mainstream media, most incidents are only reported through local media outlets.

Newspapers, NGOs, or academic institutions have created their own systems for monitoring the police use of force, however these are limited to the anti-illegal drugs campaign that is highly debated locally and internationally and which the International Criminal Court is currently investigating for Crimes Against Humanity. At the height of the “War on Drugs”, there were numerous independent monitors and cross-checking of data on police use of force — at least for the anti-illegal drug campaign specifically, — was possible. However, this number has declined over the years and now there is only one publicly available monitor on drug-related killings in the Philippines40. This is the Dahas Project of the Third World Studies Center of the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy of the University of the Philippines Diliman41.

As for other police campaigns apart from the anti-illegal drug campaign, there is no publicly available monitoring of police use of force by an academic institution, NGO, or government agency as far as the researchers know.

For the purposes of this research, media reports on the police use of force were collected following a set search strategy using inclusion and exclusion criteria. The methodology for data gathering for this research was informed by the previous research of Limpin and Siringan on the development of a method for recording drug-related killings in the Philippines42. Yet, to determine what information to codify from the available sources, that is, what data fields to build the database from, the research team relied on the research by the Global Network for Lethal Force Monitoring which has a hub at the University of Exeter. The minimum data required by this Network were the following: case code, source, type of source, link, date of publication, date of fact, time of fact, department/province/state/parish of fact, municipality of fact, place of fact, and public security institution(s) involved. Additions and refinements of the data points were made to include the name of the victim, and their age, sex, and nationality; whether the victim was injured or killed; whether the victim was civilian or PSA, and if PSA, from which agency and whether they were on duty. There were also data fields on how the harm was inflicted on the victim.

Part 3: Comparative indicators

| I-1a. CK: Number of civilians killed by law enforcement agents on duty, by gunshot | 389 |

| I-1b. CKt: Number of civilians killed by law enforcement agents, regardless of means and whether or not on duty | 464 |

| I-1c. CW: Number of civilians wounded by law enforcement agents on duty, by gunshot | 58 |

| I-1d. CWt: Number of civilians wounded by law enforcement agents, whether or not on duty and regardless of means | 83 |

| I-2. CK per 100000 inhabitants | 0.34 |

| I-3. CK per 1000 law enforcement agents | 1.00 |

| I-4. CK per 1000 arrests | 1.35 |

| I-5. CK per 1000 weapons seized | 10.33 |

| I-6. AK: Number of law enforcement officers unlawfully killed on duty by firearm | 72 |

| I-6b. AKt: Number of law enforcement officers unlawfully killed, whether or not on duty and regardless of means | 121 |

| I-7. AK per 1000 agents | 0.25 |

| A1. Percentage of homicides due to state intervention | 48.57 |

| A2. Ratio between CK and AK | 5.40 |

| A3. Civilian lethality index: Ratio between CK and CW | 6.71 |

| A4. Lethality ratio: Ratio between Civilian lethality index and law enforcement agents lethality index | 9.19 |

| A5. Average number of civilians killed by intentional gunshot, per incident | 0.76 |

The table compares indicators for deaths caused by lethal force used by public security agents. The population number used (n=115,559,009) is based on the World Bank Data for the Philippines in 202243. Indicator I-4 was calculated using the 2022 PNP Annual Accomplishment Report44 figure of 287,595 total combined arrests for the Campaign against illegal drugs, carnapping, illegal gambling, loose firearms, private armed groups, criminal gangs, smuggling and piracy, illegal logging, illegal fishing, most wanted persons, motor-riding suspects, the 2022 National and Local Elections gun ban, and the implementation of local ordinances. From the same report, Indicator I-5 was calculated using the figure of 37,668 confiscated, seized, recovered, and surrendered firearms, and Indicator A-1 using the figure of 1,015 homicides reported countrywide.

Table 2: Indicator data segregated by gender where known. Some indicators cannot be calculated, as for example a significant number of media reports do not specify the sex of the subject, and there are no reported numbers of PSAs by gender nor numbers of arrests and weapons seized by sex. Too few data are available by ethnic group to make a meaningful table.

| Indicator | Total population | Males | Females | Unreported sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-1a. CK: Number of civilians killed by law enforcement agents on duty, by gunshot | 389 | 270 | 17 | 102 |

| I-1b. CKt: Number of civilians killed by law enforcement agents, regardless of means and whether or not on duty | 464 | 322 | 25 | 117 |

| I-1c. CW: Number of civilians wounded by law enforcement agents on duty, by gunshot | 58 | 24 | 5 | 29 |

| I-1d. CWt: Number of civilians wounded by law enforcement agents, whether or not on duty and regardless of means | 83 | 38 | 6 | 39 |

| I-2. CK per 100000 inhabitants | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.03 | Data unavailable |

| I-3. CK per 1000 law enforcement agents | 1.00 | Data unavailable | Data unavailable | Data unavailable |

| I-4. CK per 1000 arrests | 1.35 | Data unavailable | Data unavailable | Data unavailable |

| I-5. CK per 1000 weapons seized | 10.33 | Data unavailable | Data unavailable | Data unavailable |

| I-6. AK: Number of law enforcement officers unlawfully killed on duty by firearm | 72 | 66 | 2 | 4 |

| I-6b. AKt: Number of law enforcement officers unlawfully killed, whether or not on duty and regardless of means | 121 | 115 | 2 | 4 |

| I-7. AK per 1000 agents | 0.25 | Data unavailable | Data unavailable | Data unavailable |

| A1. Percentage of homicides due to state intervention | 48.57 | Data unavailable | Data unavailable | Data unavailable |

| A2. Ratio between CK and AK | 5.40 | 4.09 | 8.5 | 25.50 |

| A3. Civilian lethality index: Ratio between CK and CW | 6.71 | 11.25 | 3.4 | 3.52 |

| A4. Lethality ratio: Ratio between Civilian lethality index and law enforcement agents lethality index | 9.19 | 9.53 | 1.70 | 35.20 |

| A5. Average number of civilians killed by intentional gunshot, per incident | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.55 | 0.70 |

Number of civilians killed and injured

Civilian deaths

Based on collated media reports, there were 464 civilians in the Philippines who were killed by police (on duty and off duty) regardless of means in 2022. Out of these, 389 were killed by gunshot by law enforcement agents on duty.

Most of the deaths occurred during police operations, usually under the ongoing anti-insurgency and anti-illegal drug campaigns. Alarmingly, in some cases of civilian deaths under anti-insurgency operations, the police, witnesses, the group or organization that the victim belongs to, victim’s affiliations, and/or family members provide conflicting narratives about the incident. In this report, priority was given to official police statements, which are posted through the government’s newswire services or official statements released to the media. By giving priority to the account of the police, we implicitly accept it at face value and will not engage in some haphazard investigation of its factual authenticity; this is simply not what the database and the Monitor are for.

The ongoing issues of ‘red-tagging’ and anti-insurgency in the Philippines are also beyond the scope of this report, while they are important topics for future research. The ‘Red-tagging’ of a person in the Philippines means the public insinuation, often by government officials and their social media allies, that someone is a communist or a communist sympathizer. Labeled as such, these individuals are henceforth portrayed as enemies of the state that deserve whatever harm should come their way. They are not merely delegitimized, but marked for harassment, arrest, and sometimes even extrajudicial execution.

There are incidents in the database that show the complexity of the use of lethal force and the human rights situation in the Philippines. For example, in the incident coded PH_E96, two siblings in Negros Occidental were allegedly members of the New People’s Army (NPA, the military arm of the Communist Party in the Philippines), and were killed while alledgedly armed in an encounter with the military. However, the wife of one of the siblings filed a counter report that the siblings were hog farmers who were abducted by the military. The government has denied these counter claims, and no charges were filed against any military personnel in relation to this incident. There are two other reports in the database following the same pattern, where an alleged member of a terrorist group was killed in an armed encounter, but terrorist groups themselves released counter statements claiming the killed subjects were not members of a communist organization but were ‘red-tagged’ for critiquing the government. Similar to PH_E96, in both these cases there were no charges against police.

Besides the ongoing anti-insurgency campaign in the country, there is also the issue of the anti-illegal drug campaign in the Philippines which has gained international attention from human rights groups. In the database, there were 141 civilians killed by gunshots by on-duty police in anti-illegal drug operations. These incidents usually follow a trend — the ‘nanlaban’ narrative, translated loosely as ‘fought back’, — where the civilian killed was allegedly involved in the drug trade and was about to be apprehended by undercover police acting as buyers. The civilian would sense that they are transacting with police operatives and would attempt to shoot the police, forcing the latter to fire back. The incident usually ends with the civilian suspect being killed.

With these considerations, it is recommended to add a field in the database, to tag police intervention by specific campaign.

Another notable category of civilians killed by firearms by on duty police relates to the police covering up their own crimes. In incident code PH_E19, a corporal in Albay pretended to respond to a report of murder in the area, but was later found to be the prime suspect in the incident in question, including the kidnapping and murder of an Indian national and the killing of a village councilor who witnessed the crime. The police officer, together with an accomplice, was charged with double murder and illegal abduction after witnesses reported the crime. There was also a police officer who was charged with murder and dismissed from service after killing an on-duty traffic enforcer, claiming it was self-defense (incident PH_E347).

For deaths caused by other means by on-duty personnel, 5 were killed by non-firearms:

- One minor (male, 16 years old) was killed in a vehicular chase with PSAs, when the motorcycle he was riding to evade the pursuing police officer “crashed into a gutter”

- One drowned in a hot pursuit

- One died of cardiac arrest while being apprehended by police

- One died of cardiac arrest while being investigated at a provincial police office

- One was mauled while being investigated at a municipal police office. This is the case of Gilbert Ranes, who was arrested for theft and was under the custody of the Maasin City police. While in custody, he was reportedly beaten in the head and other parts of body by Staff Sgt. Ronald Gamayon. during the investigation process . He sustained grievous bodily harm. Later, he was pronounced dead in custody. The medical examiner found severe head trauma and in Ranes’s body “hematoma and multiple abrasions”. This led to homicide charges against Gamayon, who was placed under restrictive custody and disarmed.

There are also 8 deaths whose specific method of harm was unspecified in media reports. These reports however mention that they were killed by the military during anti-insurgency operations in remote areas.

For deaths by gunshots from off-duty, but actively serving police, 15 deaths were recorded in the database. Alarmingly, some cases show behavior unbecoming of PSAs, including blatant violence against women and children, which were mostly due to personal motives:

- One woman, a wife of a police officer, was killed inside the police station while reporting her husband who was abusing her

- Two partners and two alleged lovers were killed by their husbands who were police officers, due to jealousy

- A mother and a three years old male were killed by her husband, who was a police officer, who then committed suicide

- Three were killed by drunk police

- A senior citizen (73 year old male) killed by his police officer son

There were also two civilians, including a minor (one year old, unreported gender), who were killed when a police officer’s firearm misfired.

PSAs involved in the 15 aforementioned deaths were dismissed from duty and are facing criminal charges. However, there are no update reports about the conclusion of these court charges.

Out of the 15 deaths caused by firearms of off-duty police, only 2 were off-duty police officers responding to flagrant acts: 1 was a case of gun-for-hire killed and another one who was caught in the act attempting to murder another civilian.

There were 11 deaths where it was not specified if the PSA involved was on-duty or off-duty but were still included in the database because they are actively serving. There were also 3 deaths which were not directly instigated by police but were included in the database: two were deaths within PSA detention and one was found dead following PSA contact.

In the lethal force monitor guidelines, emphasis is given to actively serving police. However, in the database, there were 7 deaths involving AWOL, discharged or dismissed, and retired PSAs. However, it is clear that for both indicators CK (civilians killed by gunshot by on-duty police) and CKt (civilians killed regardless of means by both on duty or off duty police), civilian deaths by lethal force are alarmingly high in the Philippines. Numerous incidents have also shown alarming human rights abuse against women, children, and the elderly, showing the need for further discussion on the strong culture of violence within the police force in the Philippines.

Civilian injuries

There were 83 civilians injured by PSAs, 68 of which were injured by using firearms. Besides firearms, it was found that PSAs used water cannons to disperse civilians, resulting in injury.

There was one case where the specific method of harm that caused injury was not specified in the report showing why the lack of official sources is problematic. It is reiterated that there is no centralized list or official source for civilian deaths or injuries resulting from the use of lethal force by PSAs, and that data from this report are from collated media reports. Hence, undercounting is a possibility.

Number of law enforcement officers killed and injured

There were 121 PSAs on-duty and off-duty killed, by various means (AKt). Out of this number 49% or 72 were killed by gunshots while on-duty (AK). Following a similar trend to civilians killed and injured, males still constituted the overwhelming majority of PSAs killed, which could be explained by the low number of females joining law enforcement agencies45,46. Out of 121 PSAs killed regardless of means and whether on duty or off duty (AKt), at least 115 (95%) PSAs were males. Focusing on the number of PSAs killed on duty by gunshots (AK), at least 92% or 66 out of 72 were males.

There were a further 99 “LE agents wounded on duty by firearm (attempted homicides only, excluding suicides and accidents)”. To determine the value of agents wounded on duty by firearm (AW — attempted homicides only, excluding suicides and accidents) per 1000 agents, and similarly AK and AKt per 1000 agents, the number of personnel used was that of the combined number of personnel from the police and military, which is 389,372. Hence, AW is 0.25 per 1,000 agents, AK is 0.18 per 1,000 agents, and the AKt is 0.31 per 1,000 agents.

Moreover, there are multiple cases of PSAs who are victims of suicide or accidental firing. In this database, the tag for suicide and accidental firing are separated. If there is a witness and the report clearly states that the PSA intentionally harmed themselves, it is tagged as suicide. However, for other reports which clearly mentions that the case is caused by accidental firing, the PSA death is classified as “accidental firing”. In the database, there are a total of 4 PSAs who committed suicide, all of whom intentionally shot themselves after killing a civilian. There are 13 cases of accidental firing (11 self-accident and 2 misfirings of a PSA colleague), most of which were reportedly during cleaning of service arms; these resulted in 13 deaths (11 PSAs and 2 civilians) and 3 injured (all civilians).

Indicators of use and abuse

As explained in the Data Publication by Official Agencies section, obtaining an official list of police operation reports was not possible. Due to a lack of official sources, data were drawn from publicly available media reports.47 The main tool used was Google Search using keywords in English, Filipino, and other Philippine languages drawn from an initial reading of news reports on killings committed by the police as they waged the war on drugs in 2022. The keywords and search parameters were then eventually refined to capture online news reports that give accounts of killings and injuries committed by the police and other law enforcement agents as well as incidents that resulted in the police and other law enforcement agents getting injured or killed. As a result, it is important to note that undercounting is a possibility.

The following indicators of use and abuse were computed:

- % Homicides due to state intervention

- Ratio between civilians killed by intentional gunshot by on-duty police (CK) and agents killed by intentional gunshot (excluding suicide) (AK)

- Civilian Lethality Index, or ratio of civilians killed by intentional gunshot by on duty police to civilians wounded by intentional gunshot by on duty police.

- Lethality ratio, or the ratio between Civilian lethality index and LE agent lethality index

- Average of civilians killed by intentional gunshot per incident

The indicator of Civilians killed per 1,000 agents (I-3) cannot be determined due to unavailability of the total number of active PSAs in the country. There is no centralized database for the number of armed and uniformed personnel for the different LEAs in the Philippines. While each agency is required to submit an annual report to the Commission on Audit containing the total number of active personnel under their agency, this number does not separate the total number of uniformed personnel who are provided with firearms, from non-uniformed personnel conducting other functions such as administrative, maintenance, or logistics.

To derive the ratio of civilians killed per 1,000 arrests and per 1,000 weapons seized, data from the 2022 PNP Annual Report was used48. Based on the report there were 287,595 arrests in 2022 by the police, resulting in a rate of 1.43 or almost 2 civilians killed per 1000 arrests. Compiled data on number of weapons seized in 2022 show that there were 37,668 firearms seized from campaigns against lost firearms, private armed groups, criminal gangs, local terrorist groups, and 2022 national and local election gun ban, resulting in a rate of 10.88 or around 11 civilians killed per 1,000 weapons seized. The same report also noted that there were 1,015 homicides in the country in the same year. Based on media reports collated, accounting for flagrancy, police check, forces operations, PSA mediation in civil confrontations, and social protests there were 440 homicides against civilians and 53 against agents for a total of 493 homicides in the database which could be accounted to state interventions.49 Comparing the total number of homicides in 2022 vis-a-vis the total number of homicides by state intervention in the lethal force monitor database for the Philippines in 2022, 48.57% of homicides are due to state interventions. It is important to note however, that data in the database is collated from media reports due to lack of official sources, as explained in the section Data Publication by Official Sources of this report.

Deaths for both civilians and PSAs are tagged as homicide by state intervention if they occurred in the following circumstances, as provided for by the Global Network for Lethal Force Monitoring: flagrancy, police checks, forces operations, civil confrontations, and social protests.50 Ambushes against forces and other situations outside of the aforementioned categories are not counted as homicides due to state interventions, because these were not initiated by law enforcement agents during operations, hence these are not state interventions.

If the homicides are segregated by type of police intervention, both civilian and PSA homicides due to state interventions occur during forces operations including those in the anti-drug and anti-insurgency campaigns. As discussed in the sub-section for Civilian Deaths, it is recommended to add a sub-item to categorize incidents by specific type of campaigns.

Table 3: Civilian and PSA deaths and injuries due to police interventions.

| Type of police intervention | Civilian deaths | PSA deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Civil confrontation | 2 | 3 |

| Flagrancy | 50 | 7 |

| Flagrancy, civil confrontation | 5 | 1 |

| Flagrancy, forces operation | 17 | 0 |

| Flagrancy, police check | 1 | 0 |

| Forces operation | 341 | 35 |

| Forces operation, ambush against forces | 2 | 5 |

| Forces operation, police check | 11 | 0 |

| Police check | 9 | 2 |

| Police check, ambush against forces | 2 | 0 |

| Total | 440 | 53 |

Using the World Bank Data on the 2022 population of the Philippines51 to compute the indicators of use and abuse, we find 0.40 civilians were killed per 100,000 inhabitants. The World Bank Data was used instead of the national census because the latest census by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) was in 2019. However, when the PSA data is used, a similar ratio of 0.43 per 100,000 is found.

Comparing the number of homicides due to state intervention for civilians and PSAs, the number of civilians killed in state interventions is more than 8 times higher compared to PSAs killed due to state intervention. There were a total of 440 civilians and 53 agents who died due to state interventions, for a total of 493.

Data on the total number of homicides for 2022 was obtained from the 2022 PNP Annual Accomplishment Report. Based on this report there were 1,015 reported homicides in the country for 2022. Using this data, it was found that 48.57% of reported homicides in 2022 were due to state interventions. It is important to note however, that the data for the total number of homicides in 2022 was based on an official data source, specifically the PNP annual report. It must be also mentioned that the report has a separate entry for murder committed in 2022: 4,272. If the combined number of murder and homicide will be the denominator, that is, 5,287, then the killings that could be attributed to the state’s action will now be 9.32%. On the other hand, there is no official source for the number of civilian deaths and PSA deaths and the database is based on collated media reports. The data for the number of civilian deaths and PSA deaths cannot be crosschecked against any official source.

As previously mentioned, one challenge in using media reports for data collection is that the sex of the subject is sometimes unreported. Similarly, the 2022 PNP Annual Report does not disaggregate data by sex, and the number of homicides for males versus females is not available. Due to these reasons, the indicator for percentage of homicides due to state intervention, disaggregated by sex cannot be computed.

Lethality Ratio

Data for the ratio between civilians killed and agents killed, the civilian lethality index, and the ratio between civilian and agent lethality indices were computed using collated media reports due to the unavailability of official sources. All three indicators are higher compared to other countries, which shows that the number of civilian deaths due to lethal force is out of proportion. As mentioned in the previous subsection on civilian deaths, intentional gunshots by on duty agents are the primary cause of deaths. In the last indicator, it is found that the average number of civilians killed by intentional gunshot is around one per incident.

Proportionality of civilian killings

Comparing the rate of deaths for civilians and agents, there is disproportionality in civilian killings with a ratio of 5.70 (CK/AK) and lethality ratio of 9.87 (Civilian lethality index/Agent lethality index). These are alarming ratios, in view of the 2021 update of the PNP Operations Manual, which states that “Lethal force will only be employed when all other approaches have been exhausted and found to be insufficient to thwart the life-threatening actions or omissions posed by armed suspect or law offender”52. Specifically, the use of firearms is justified only when there is imminent danger of death or injury to a police officer or third parties, or when agents are outnumbered and overpowered. There is also a high civilian lethality despite orders of maximum tolerance in the PNP Operations Manual.

As mentioned in the previous subsections, computing the disproportionality proved challenging. While it can be said that males comprise the majority of those killed and wounded, for both civilian and police sides, it is difficult to establish disproportionality in other indicators of use and abuse due to media reports not specifying the sex of the report subject and the lack of official sources to counter-check this data. Moreover, even available official sources such as the PNP Annual report does not disaggregate data by gender.

Besides disproportionality by sex, disproportionality by ethnicity was not computed because these are not mentioned in media reports. A confounding factor in the Philippine context is that an individual usually belongs to more than one ethnolinguistic group, and there have not been previous reports that violence was directed towards specific ethnolinguistic groups. Movement and migration from one region to another is also very common.

Besides disproportionality by sex, disproportionality by ethnicity was not computed because these are not mentioned in media reports. A confounding factor in the Philippine context is that an individual usually belongs to more than one ethnolinguistic group, and there have not been previous reports that violence was directed towards specific ethnolinguistic groups. Movement and migration from one region to another is also very common.

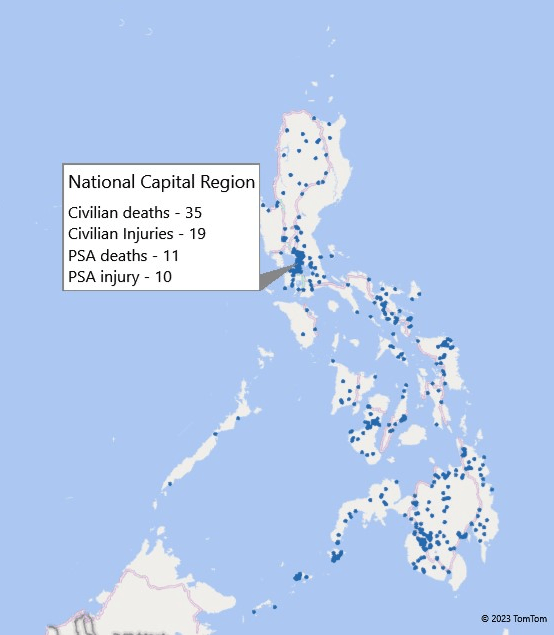

As an alternative, a map of all known incidents of Police use of force in 2022 is reproduced here. The National Capital Region is observed as a major hotspot for incidents, with 35 civilian deaths, 19 civilian injuries, 11 PSA deaths, and 10 PSA injuries.

Summary and recommendations

This study assessed the police use of lethal force in the Philippines for 2022 in three aspects: Legal frameworks in place relating to police use of force, policies and procedures on data collection and analysis in relation to lethal force, and comparative indicators in the use and abuse of lethal force in the country.

On legal frameworks (Part 1):

We recommend that the Office of the President should:

- Lead in ending the culture of impunity by suspending “License to Kill” under the Anti-Illegal Drug Campaign, directing concerned agencies such as the Commission on Human Rights and the Department of Justice through the National Bureau of Investigation to conduct full and transparent investigations of human rights violations by state actors, and support recommendations of the CHR and DOJ, to uphold commitment in protecting and respecting human rights.

- Spearhead a holistic, human-rights based strategy towards national development that has more focus on social determinants and less on a heavy-handed approach to law enforcement.

- Welcome independent investigations on extrajudicial killings in the Philippines and support efforts of the international community in the global protection of human rights.

- Provide a specific list of law enforcement agencies and personnel ranks that are allowed to possess service firearms and weapons, ensuring that service firearms of discharged, dismissed, and AWOL agents are promptly and completely surrendered.

- Ensure implementation of routine inspection of service firearms and investigate alleged misfirings that resulted from service arm cleaning.

- Ensure that regulations on the use of force, such as the continuum on the use of force, wearing of body cams, proper incident documentation and impartial investigations, are fully implemented.

- Strengthen the People’s Freedom of Information, through thorough review of the detailed list of exceptions to the FOI and the quality of data released through FOI requests.

On policies and procedures (Part 2):

As stated in the report, there is much to improve in terms of data collection on the use of lethal force in the country and in terms of data analysis. There is a lack of transparency on data on the number of PSAs and Civilians killed or injured due to lethal force and the progress with DOJ independent investigations on the use of police force in the anti-illegal drug campaign or other police intervention campaigns.

We recommend that the PNP should:

- Be subject to an automatic death investigation by a third party, either the CHR or the NAPOLCOM, in all cases where agents of the State are involved. At present, if there is no complainant or complaint before the police, homicide cases are not worked on unless there is a public outcry, such as if the killings proved to be a sensational story in the media. It must be recalled that any police officer’s discharge of a firearm is supposed to be subject to an automatic review of the police’s own IAS; the Police has not released any data to suggest that this mandate is being carried out.

- Resume the regular public release of statistics on the use of lethal force for the anti-illegal drug campaign through #RealNumbersPH or other publicly available material, ensuring that data is of high quality and data collection and analysis methodology is explained.

- Regularly release written official reports on the use of lethal force in the Philippines, including complete statistics on the police use of lethal force in all police campaigns, investigations, and interventions executed through interagency efforts. This is however a tall order, given the police’s and the military’s extensive list of exceptions to Freedom of Information requests for access as provided for by Executive Order No. 2 (2016) by then-president Rodrigo Duterte, and updated by Memorandum Circular No. 15 (2023) by the current Marcos administration.

- PNP HRAO should resume/continue engagements with Civil Society Organizations to discuss police use of force and human rights concerns including issues of arrest, ill treatment, deaths in detention, alleged abduction by police, and alleged misfirings.

- Ensure proper implementation of human-rights based policing based on the PNP standard operation manual and Human Rights-Based Policing Manual, as well as consequences for agents violating these guidelines.

We recommend that the DOJ should:

- Conduct impartial and prompt investigation of civilian deaths directly involving PSAs or following police contact.

We recommend that CSOs should:

- Engage in discussion on the creation of comparable monitoring systems for lethal force in the Philippines, conduct independent monitoring on the use of lethal force in the Philippines, and make these publicly available for critique and cross-validation.

On comparative indicators (Part 3):

We recommend that LEAs should:

- Disaggregate data by sex and age in accomplishment reports, such as in the case of the PNP Annual Accomplishment Report, in line with gender mainstreaming rules and regulations

- Include the total number of active uniformed personnel in COA reports and Annual Accomplishment Reports of different LEAs, with data disaggregated by sex in accordance with gender mainstreaming policies

For future lethal force monitoring in the Philippines and in the LFM network, those involved should:

- Review the operational definition of lethal force, to include cases of alleged misfiring of PSAs against civilians or alleged misfiring of PSA or suicide towards themselves

- Include a sub-item to tag police intervention by specific police campaign (i.e. anti-insurgency or anti-illegal drugs)

References, data sources and downloads

This page is a slightly edited version of the 2024 Philippines Lethal Force Monitor report (PDF, 160KB).

1 Christopher Lloyd Caliwan, “3 Detainees at PNP Custodial Center Killed After Escape Try”. Philippine News Agency, 9 October 2022, online: https://www.pna.gov.ph/

2 The Official Gazette, The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines, 1987,

https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/#:~:text=The%20maintenance%20of%20peace%20and,and%20State%20shall%20be%20inviolable.

3 Idem.

4The Official Gazette, Revised Penal Code of the Philippines, 1930,

https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1930/12/08/act-no-3815-s-1930/.

5 The Official Gazette, Republic Act No. 6975, 1990,

https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1990/12/13/republic-act-no-6975/.

6 Internal Affairs Service, Philippine National Police, Tanglaw 2023. Available at: https://ias.pnp.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/061323-PNP-IAS-Annual-Report_Pages_ver3.pdf.

7 Philippine National Police, Revised Philippine National Police Operational Procedures, 2021, p 8. Available at:

https://pro8.pnp.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/PNP-POP-2021.pdf.

8 Ibid, p 12.

9 Philippine National Police, PNP Guidebook on Human Rights Based-Policing, 2013, p 108. Available at:

https://acg.pnp.gov.ph/main/images/downloads/EBooks/GUIDEBOOK.pdf.

10 Commission of Human Rights, On the Denunciation of and Withdrawal From International Treaties To Reimpose the Death Penalty, 2017, Quezon City, Philippines. p 1. Available online at:

https://chr.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Denunciation-of-and-Withdrawal-from-International-Treaties-to-Re-impose-the-Death-Penalty.pdf.

11 Ibid, p 2.

12 Senate of the Philippines, 19th Congress, Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT), 2011,

https://legacy.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2011/1213_legarda1.asp#:~:text=Chronology%20of%20Events-,The%20Convention%20Against%20Torture%20and%20other%20Cruel%2C%20Inhuman%20or%20Degrading,primary%20international%20anti%2Dtorture%20mechanism.

13 United Nations, Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Unhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, 2016,

https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2FPPRiCAqhKb7yhsgznA20o03W4ewclL3J%2FFce9G6Dau8FH2NIMXqB31lXxG%2BRJi%2FYd2%2Brduk5zGugrupVQWdVg4Xn9zony3mNy4%2BHi7oXRA3X18HlXYdDTSdr5.

14 Senate of the Philippines, 19th Congress, Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture (OPCAT), 2011,

https://legacy.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2011/1213_legarda1.asp#:~:text=Chronology%20of%20Events-,The%20Convention%20Against%20Torture%20and%20other%20Cruel%2C%20Inhuman%20or%20Degrading,primary%20international%20anti%2Dtorture%20mechanism.

15 International Criminal Court, ICC Statement on The Philippines’ notice of withdrawal: State participation in Rome Statute system essential to international rule of law, 2018,

https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/icc-statement-philippines-notice-withdrawal-state-participation-rome-statute-system-essential

16 Jodesz Gavilan, “International Criminal Court and Duterte’s bloody war on drugs,” Rappler, June 26, 2022, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/timeline-international-criminal-court-philippines-rodrigo-duterte-drug-war/.

17 International Criminal Court, Statement of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda concerning the situation in the Republic of the Philippines, 2016. Available at:

https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/statement-prosecutor-international-criminal-court-fatou-bensouda-concerning-situation-republic.

18 International Criminal Court, Statement of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda, on opening Preliminary Examinations into the situations in the Philippines and in Venezuela, 2018. Available at:

https://www.icc-cpi.int/news/statement-prosecutor-international-criminal-court-fatou-bensouda-opening-preliminary-0.

19 https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/itemsDocuments/181205-rep-otp-PE-ENG.pdf

20 https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/CourtRecords/0902ebd1803d051c.pdf

21 CNN Philippines, ‘No appeals pending’: Marcos refuses to cooperate with ICC on drug war probe, 2023. Available at: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2023/7/21/marcos-icc-drug-war-probe.html.

22 Association of Southeast Asian Nations, ASEAN Human Rights Declaration and the Phnom Penh Statement on the Adoption of the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration (AHRD), 2013, Jakarta, Indonesia. Available online at:

https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/6_AHRD_Booklet.pdf.

23 Association of Southeast Asian Nations, 36th Meeting of the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, 2023. Available online at:

https://asean.org/36th-meeting-of-the-asean-intergovernmental-commission-on-human-rights/ (accessed 25 September 2023).

24 BBC, “Philippines drug war: Police guilty of murdering Kian Delos Santos”, November 29, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46381697. See also Jairo Bolledo, “Even after death, Kian delos Santos remains a victim of injustice”, Rappler, February 7, 2023, https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/kian-delos-santos-remains-victim-injustice/.

25 https://mb.com.ph/2023/6/1/ias-must-operate-freely-amid-monstrous-corruptive-influence-of-drugs-on-pnp-house-leader

26 https://www.philstar.com/nation/2022/09/20/2210912/pnp-ias-chief-faces-sexual-harassment-case

27 https://www.philstar.com/nation/2023/12/05/2316519/pnp-downgrades-ias-chiefs-penalty

28 National Police Commission, Approving the Activation of the Human Rights Desks at the Different Levels of Command in the Philippine National Police”, 2009. Available at: https://napolcom.gov.ph/pdf/res%202009-072%20.pdf.

29 Philippine National Police, Office of the Chief PNP, Incident Recording System, 2012, SOP Number 2012-001, Camp Crame, Quezon City. Available online at: https://didm.pnp.gov.ph/images/Standard%20Operating%20Procedures/SOP%20ON%20INCIDENT%20RECORDING%20SYSTEM.pdf.

30 #RealNumbersPH, “#RealNumbersPH Year 6,” Facebook, June 21, 2022,

https://www.facebook.com/realnumbersph/photos/pb.100067598889220.-2207520000/2215676548613871/?type=3

31 Philippine National Police, The Directorate for Plans, PNP People’s Freedom of Information (FOI) Manual, 2018, Cam BGen Rafael T Crame, Quezon City. Available online at: https://didm.pnp.gov.ph/images/DIDM%20Manuals/FOI-HANDBOOK-JULY-2018.pdf

32 Philippine National Police, PNP Annual Accomplishment Report 2022, 2022, available online at: https://pnp.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/AAR-2022-FINAL-013123.pdf

33 Joel F. Ariate Jr. and Larah Vinda Del Mundo, “Who says Marcos war on drugs is ‘bloodless’?” Vera Files, October 24, 2023. Available online at: https://verafiles.org/articles/who-said-marcos-war-on-drugs-is-bloodless.

34 Philippine National Police, Human Rights Affairs Office, PNP Human Rights Police Directions and Guidelines, 2007, available online at: https://hrao.pnp.gov.ph/mandate-and-functions/.

35 Philippine National Police, Human Rights Affairs Office, Accomplishment Report PNP Human Rights Affairs Office Human Rights-Based Policing Programs, 2020. Available online at: https://hrao.pnp.gov.ph/2020-accomplishments/.

36 Commission on Human Rights, Report on Investigated Killings in Relation to the Anti-Illegal Drug Campaign, 2022, p. iii

37 Ibid. p. 38

38 Ibid. p. 41

39 https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/861256/marcos-won-t-cooperate-with-icc-over-sovereignty-jurisdictional-issues/story/